Founded in 1917, Golden Gate Bird Alliance engages people to experience the wonder of birds and translate that wonder into conservation action. We offer over 150 free bird walks each year, monthly guest speakers, and volunteer opportunities restoring habitat, educating young people, and engaging in conservation advocacy and citizen science. See our website or sign up for our email newsletters to learn more.

A Chronological Osprey Season

Check out our Traditional FAQ!

While every nesting season is different, there are fundamental elements that remain the same. Follow along with Rosie and Richmond on a typical year of nesting activity. See what makes the current season unique.

First, a Little History

When did Rosie and Richmond begin nesting on the Whirley crane? According to Tony Brake, local Osprey expert: “I didn’t discover the Osprey nest on the crane until July 2011. Since there were no nestlings/juveniles at the time, it was apparent the nesting failed that season. I learned from a former docent on the ROV, a GGRO hawkwatcher, that the first year it was used was in 2010 and they fledged at least one. A Google Streetview image showed the nest wasn’t present in 2009.

“The Richmond Yacht Club nest was installed in 2016, and the male was almost certainly Richmond, who overwintered 2016-17. As the 2017 nesting season approached, Richmond spent time at both nests. When Rosie showed up (3/5/17), he proceeded to pair with her at the Whirley Crane nest, since the previous male apparently didn’t return. He had previously returned in mid-late February. Once the female returned to the RYC nest, Richmond also spent time there, with copulation occurring with both females. Eventually, another male showed up who paired with the RYC female, and Richmond settled on the crane nest. This pattern repeated the next two years.”

How old are Rosie and Richmond? They are believed to have bred in 2016, as stated above, when they would have been at least three years of age. Ospreys may live into their late twenties, but 10% of the adult population perish each year, and the average life expectancy for Ospreys in the wild is 8-10 years.

Pre-Season

The season usually begins when Rosie returns from migration. It’s unknown where she goes, but she almost certainly goes south for the winter. Richmond remains in the area, one of a few (GGAS’s 12/31/22 bird count tallied 12 Ospreys) who overwinter in the SF Bay Area. The pre-season, for our purpose, is from January 1 to Rosie’s return.

Migrating Ospreys begin returning to the area in February.

Richmond may be seen more frequently around the nest in February.

The Richmond Yacht Club Osprey nest platform (set up in 2015 and first used in 2016) is about a mile from the nest. Richmond may interact with the Osprey(s) there, as he most likely nested there in 2016.

Other floaters (unpaired breeding-age adult Ospreys) may visit the area or nest to investigate. Richmond occasionally begins a bonding process with floater females.

Rosie and Richmond: The First Few Weeks

If Richmond has been interacting with any other females, Rosie’s arrival may mean she must defend her nest from them. Richmond may or may not join in.

Rosie has returned between 154-178 days after she departed in the fall.

Richmond will mantle in Rosie’s presence, which indicates his willingness to bond with her.

R&R typically spend a couple of weeks getting to know each other again and renewing their bond.

Osprey copulation is the act of attempting to achieve a cloacal kiss (often referred to as CK on chat). According to Birkhead and Lessels in 1988, Osprey “pairs copulated frequently, on average 160 times/clutch (range: 88–338), but only 39% of these resulted in cloacal contact.”

Richmond begins bringing fish to Rosie, although Rosie continues to fish on her own as well.

Nest Building

During the first month after Rosie’s return both Rosie and Richmond begin to bring nesting materials to refurbish the nest. Some years they have a lot of work to do, as they did in 2022, when Ravens removed many sticks to build their own nest nearby.

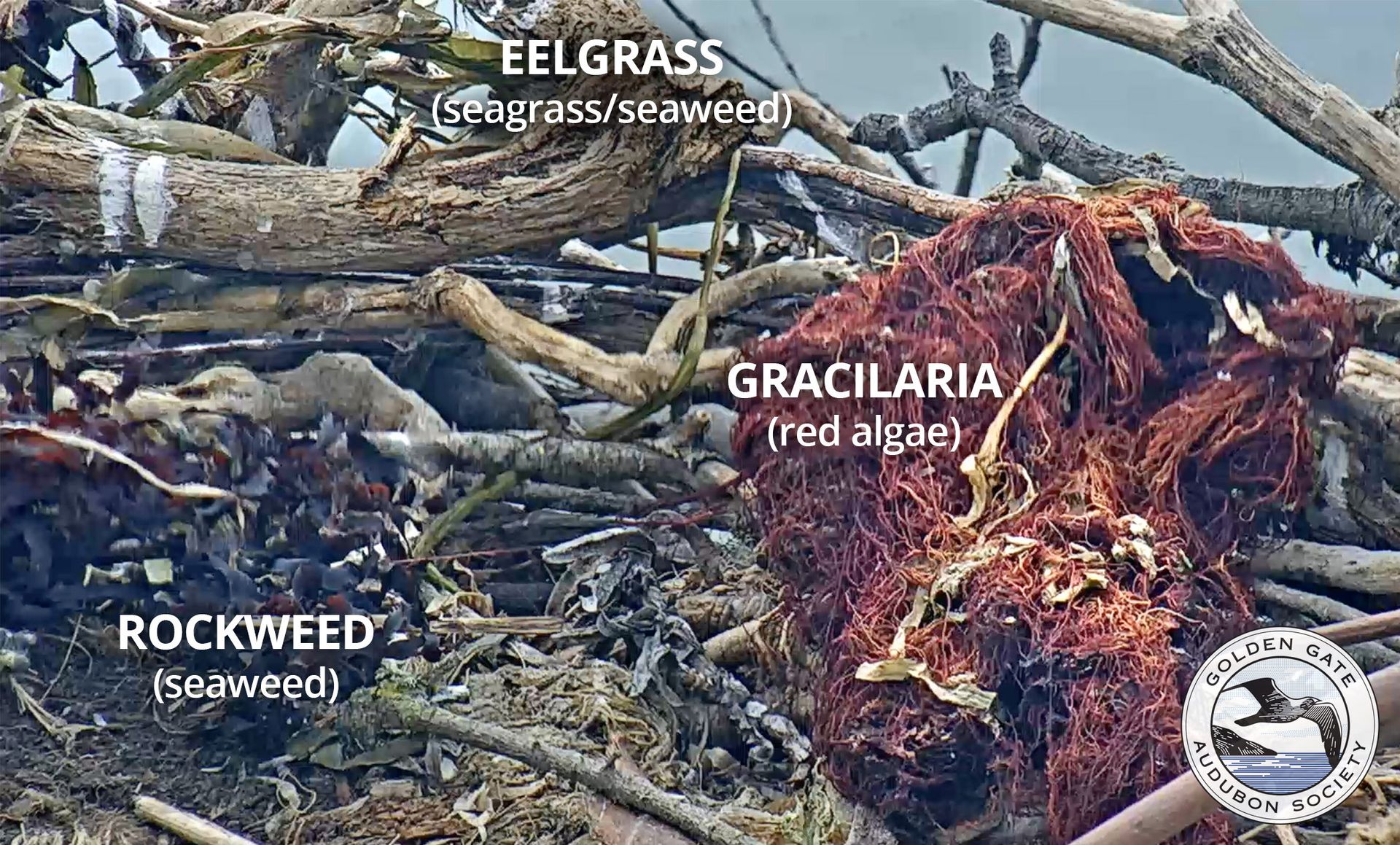

Materials brought to the nest include sticks, eelgrass (Richmond has some of the richest eel beds in the SF Bay Area), rockweed, Turkish towel, dried iceplant, bird carcasses, etc. Nest vegetation.

Eelgrass Zostera marina (a flowering plant) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zostera_marina. See also this video about the importance of eelgrass to migrating birds.

Gracilaria pacifica http://www.sfbaylivingshorelines.org/PDFS/09-Macroalgal.pdf

Rockweed Fucus distichus https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fucus_distichus (There is an invasive species, Ascophyllum nodosum, which is sometimes also called Rockweed)

Turkish towel Chondracanthus exasperates https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chondracanthus_exasperatus.

Bird carcasses are seen by Ospreys as nesting material. Ospreys do not kill other birds. In one rare instance Rosie and the two nestlings appeared to nibble at a fresh carcass, likely intended as nest material, but this is very unusual.

Egg Development

R&R copulate with more frequency as egg-laying time approaches.

It only takes a few days for Rosie to develop an egg. The time from fertilization of the ovum to laying is about 24 hours in chickens, and most of that is in formation of the shell. While there are no studies for Ospreys, here is a related study for Bald Eagles, which are similar. And as the fact sheet shows, the time between each egg laid by Rosie is usually between 67-75 hours.

One can tell Rosie is ready to lay eggs when they have begun to shape the center of the nest into a bowl shape. Soon before egg laying Rosie will usually spend time down in the nest similar to incubating. This tendency is termed broodiness.

Rosie has always laid three eggs, but it should be noted that Ospreys sometimes lay four eggs. There have been two occurrences of four young fledged from SF Bay nests since they have been monitored from 2012. There may have been other four-egg clutches, where eggs didn’t hatch or nestlings didn’t last long enough to be observed.

Osprey eggs

Will Rosie ever stop laying eggs? According to Tony Brake, local Osprey expert: “Ospreys usually increase [egg] productivity as they age, at least up to a point. They just don’t seem to die of old age. I suspect that mishap or disease is more likely the main cause of mortality.”

Maculation refers to the identification of individual eggs based on the pattern of pigment deposited as the egg exits Rosie. Here’s an excellent article on how eggs get their colors.

PBS’s Nature has a wonderful episode about eggs: The Egg, Life’s Perfect Invention

Here is an article about how chicks get oxygen inside the egg.

Egg Incubation

Soft incubation is the behavior where the first and second eggs are incubated sporadically until the last egg is laid. This results in a shorter interval between hatchings than would occur if all eggs were incubated continuously from laying. This way there is not such a disparity in nestling ages, since there is usually a six-day difference in when the first and third eggs are laid. The last hatched is already at a disadvantage in feeding initially. Not a problem when food is abundant, but when food is limited, the younger nestling(s) may risk starving.

Even during hard incubation the adults may not always incubate continuously, especially during warm weather. Bay Area temperatures are often in the low 50s overnight. With the insulating properties of the nest plus likely heat from decomposition of the nest material, eggs are usually much warmer than that. Rosie is quite capable of sensing egg temperature. Eggs are much more sensitive to high temperatures.

Once three eggs are laid, Rosie often refuses copulation attempts. After a week or two Richmond no longer makes the attempt.

According to the fact sheet, incubation lasts an average of 38 days for the first egg, 36.2 days for the second egg, and 35.7 days for the third egg.

Both Rosie and Richmond incubate the egg. Sometimes at the same time, although Richmond is not really incubating, just sitting next to Rosie.

During incubation, Richmond assumes all responsibility for catching fish for Rosie. The rate of fish deliveries during incubation is usually the lowest of the season.

Hatch

This site counts a chick as officially hatched once at least half the shell has fallen off the chick and the head can be seen wobbling about.

Sometimes pips (the hole where the chick inside has first broken through the shell) can be seen before the chick hatches. Because the cameras are lit at night with infrared lighting, the colorful speckles visually disappear, and pips can be seen more easily.

Chicks break out of the shell using their egg tooth, a calcium deposit on the outside of the beak. The egg tooth slowly wears off over the next few weeks.

Egg tooth

Chicks are first fed when fish are available. According to the fact sheet, it can range from a couple hours to 17 hours. If the chick hatches in the late evening, it may not be fed until the next morning.

Some eggs may not hatch. This occurred in 2022, where the first egg did not hatch. There are numerous reasons for failure to hatch, and no way to determine why without direct examination for the presence or abcense of an embryo. Here is an extensive study of unhatched eggs in Blue Tits and Great Tits. Infertility was a small fraction, as well as more of an observational tabulation for Bald Eagles.

Rosie may eat some of the egg shells to replace the calcium required for egg production.

Chicks: Week 1 (0–7 days)

See The first week | May 23, 2022 for a video of the first week in an Osprey chick’s life.

See also Bobbleheads | May 20, 2022

Developmental changes include: eating, preening, and sibling rivalry may begin toward the end of the week. Rosie carefully covers the chicks to keep them warm, where her downy feathers trap in body heat while still allowing the chicks to breathe.

Chicks: Week 2 (8 to 14 days)

See Week 2 | May 31, 2022 for a video of the second week in an Osprey chick’s life

Developmental changes include: more frequent sibling tussles, moving around the nest further, interest in picking up pieces of fish, body growth, and emergence of darker feathers.

Chicks: Week 3 (15–21 days)

See Week 3 | June 7, 2022 for a video of the third week in an Osprey chick’s life.

Developmental changes include: continued sibling fights, ranging further afield, first wing flapping, and body and feather growth.

Chicks: Week 4 (22–28 days)

See Week 4 | June 14, 2022 for a video of the third week in an Osprey chick’s life.

Developmental changes include: continued sibling fights, more awareness of the outside world, early wing flapping, more standing/walking, self feeding, and rapid body and feather growth.

Chicks: Week 5 (29–36 days)

See Week 5 | June 21, 2022 for a video of the third week in an Osprey chick’s life.

Developmental changes include: the end of sibling fights, no longer fitting under Rosie (although she continues to lie with them on the nest at night), growing interaction with and awareness of the outside world, wing flapping sessions of 10-15 seconds, standing/walking more often, little change in self feeding, more vocalizations, and slower body growth but increased feather growth. Nestlings are also able to thermoregulate themselves by this time, so Rosie may begin to leave the nest more often, while staying nearby.

Chicks: Week 6 (37–42 days)

See Week 6 | June 28, 2022 for a video of the third week in an Osprey chick’s life.

Developmental changes include: longer wing exercise sessions lasting 15-30 seconds, standing/walking more often, a spurt in feather growth. Self feeding has advanced to easily downing fish tails and figuring out how to eat fish left on the nest. They still prefer to be fed. Vocalizations are much louder and more robust. Rosie continues to lie with them on the nest at night but may leave the nest more often for longer periods.

Chicks: Week 7 (42–49 days)

See Week 7 | July 5, 2022 for a video of the third week in an Osprey chick’s life.

Developmental changes include: The two most significant changes are the increase in flight practice — perhaps being close to hovering by the end of the week — and in self feeding. Richmond may begin to bring live fish, and Rosie may also leave fresh fish for them to eat on their own. They may be more territorial about the food, resulting in fish fights. They begin to participate in nest defense and are more often awake and aware. Clouds of down feathers shed from the juveniles fill the nest. By the end of the week Rosie may spend at least half the night upright on the nest or on the lower boom cable.

Chicks: Week 8 (50–56 days)

See Week 8 | July 12, 2022 for a video of the third week in an Osprey chick’s life.

Developmental changes include: self-feeding skills advance to where the nestlings are able to dispatch live fish brought to the nest. They will pancake upon hearing an alarm call from Rosie or Richmond, and begin giving alarm calls themselves. Other firsts may include standing upright, standing on one leg, and sleeping upright with heads tucked. This week is often when the nestlings will fledge, as most nestlings from this nest have fledged between 51-60 days of age (females often take a little longer than males due to higher weight).

Bullet 3: For the purpose of productivity studies, Ospreys are considered fledged when they reach 80% of usual fledging age, about 45 days.

Banding and Naming

The Bird Banding Lab at USGS permits all banding of wild birds in the US. Numerous agencies, organizations, and individuals may hold permits for banding various species. For this nest, banding has been done by GGRO Banding Manager Teresa Ely, who is permitted by USFWS and CDFW for banding. All birds banded under USGS auspices get a stainless steel band with a unique band number. The more easily read color bands are “Auxiliary Bands” which require an additional permit. Both are compiled by the USGS BBL. See also the GGAS article Osprey Banding Explained.

If you ever see a banded bird please report it at www.reportband.gov. They will respond with information on the banded bird, and report it to the original banding organization.

Naming usually occurs around the time the nestlings are banded. To submit names for the newest cohort check the Live Chat or Facebook page for more information.

Post Fledge

Ospreys instinctively know how to fish. We know this because nestlings that go into care may not have adults available to feed them when they return to the wild. There is a lot of trial and error, and if the adults are around fledglings will watch and learn. Each juvenile learns how to fish on its own schedule.

Juvenile Ospreys take a few days to achieve confidence flying, after which time they are seen at the nest less often. They usually appear in the evening and will continue to be fed by Richmond and Rosie for one to two months. The age at which they are last seen on the nest ranges from July 28 (a male) to September 11 (a female). Females average 109 days around the nest compared to 90 days for male nestlings.

Where they have been tracked, juveniles tend to wander around for some time before heading off on migration. The departure dates for Oregon and British Columbia adult female Ospreys that have been tracked range from Aug 28 to Sept 24. Only a single male was shown as Sept 1. A juvenile from the 2019 cohort, Peace-up (banded WP), was seen Oct 1 in Corte Madera, CA, approximately eight miles from the nest.

Migration: Where Do They Go and When Do They Return?

There is much more data on east coast Ospreys than west coast, but Oregon and Canadian Ospreys are known to migrate to Baja California, Mexico, Central America, and even as far south as Columbia. See also these two maps of Osprey migrations. from Osprey Watch and All About Birds.

When juvenile Ospreys first leave their natal nest, they spend about 18 months away, before returning to the area they hatched.

Post Season

The season is considered over once Rosie leaves on migration. Richmond will usually stay near the nest for at least a week, then he may find a nearby location to overwinter, coming to check on the nest from time to time. The 2022-23 winter was unusual in that he was seen in the area most of the off season. The post season, for our purposes, ends December 31.

Fishing Through the Season

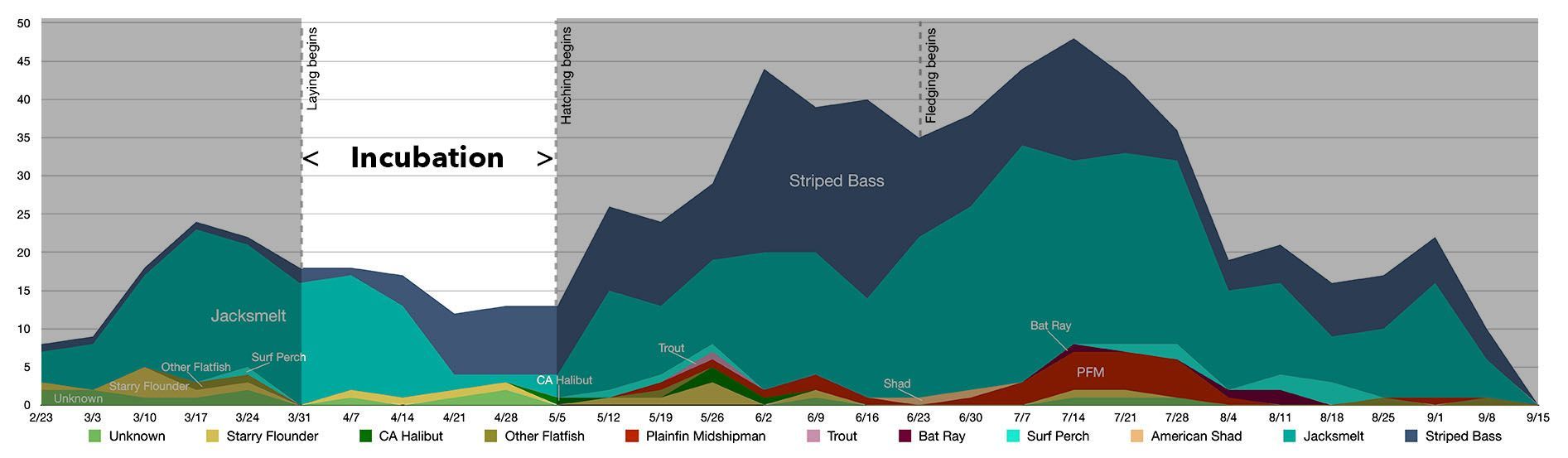

The Fish Counting Matrix (found below the Live Chat) is an ongoing community science project with the aim of counting and identifying every fish brought to the Whirley Crane, roughly 700 fish in a typical year. Fish deliveries are documented by Live Chat participants, and recorded in the Matrix in a constantly updated Osprey’s-eye view of local fish populations around the Bay and how they fit into our Ospreys’ diet.

Studies indicate Ospreys need about 400 grams of fish (of average caloric content) per day, but the family’s total dietary requirements vary across the season. While Rosie is sedentary, incubating the eggs, just a couple of fish a day is enough to meet the two Ospreys’ needs, but later, while the chicks are growing, Richmond and Rosie may need to bring six or more fish to the nest each day.

The fish species most seen at the nest is the lithe and lively Jacksmelt, highly nutritious and plentiful in Bay waters near the nest, with second place going to Striped Bass, which are calorically leaner but can sometimes reach massive size. With the help of Fish Matrix volunteers, we also regularly record Black Perch, Starry Flounder, Brown Rockfish, California Halibut, and American Shad, as well as more unusual species such as Bat Rays, Lingcod, and even, in 2022, a small shark!

The data collected in the Fish Matrix allows us to observe trends across the season, or to compare different seasons. For instance, the nocturnal, bioluminescent Plainfin Midshipman, a Live Chat favorite, usually start arriving as part of the daily catch in May, and their numbers peak during the month of July. Midshipman, incidentally, are among the few species of which Rosie catches more than Richmond.

Seasonal variations can also provide intriguing clues to the Ospreys’ foraging activities and range. In the drought years of 2020-2021 higher salinity in the Bay kept the Starry Founder from their normal migration down from the Sacramento River Delta, and so very few made it into Rosie and Richmond’s pantry those years. In 2020 Richmond surprisingly started bringing large numbers of rainbow trout to the nest – including the eye-catching lightning trout – followed soon by Rosie doing the same. The trout were determined to be coming from San Pablo Reservoir, 6.5 miles to the east, planted there for sport fishing. Then, during the 2022 season, Rosie surprised us again, bringing 15 large goldfish to the nest, likely taken from nearby private ponds.

Wounds

Wounds on Osprey legs heal fairly quickly. According to Tony Brake, local Osprey expert: “We captured a juvenile that had monofilament from plastic cord tethering it to the nest in 2014. The line had cinched and embedded deeply into the skin, causing a nasty wound. After cleaning it up and returning the juvenile to the nest the wound resolved readily. Blood will likely remain until another dip in the water.”

Regarding stings from Bat Rays on 2019’s Kiskasit’s (banded ZK) legs, Tony said “From my experience with stings, they are usually superficial. Very painful in the short term because of the venom. I imagine the wound will heal fairly quickly.”

Richmond’s Talon Injury

In March 2022 it was noted that Richmond had broken off his rear talon. This affected his ability to fish during the 2022 season. While Rosie made up for a small percentage of the difference during periods when Richmond should have been the sole provider, the number of fish brought to the nest in 2022 (two nestlings to support through July 16, then one nestling through August 8) was half that of 2021 (three nestlings supported through July 28, two supported through August 16, then only one nestling through August 24).

Intruders

Often “intruders” are simply Ospreys flying over, going about their business. In occasional cases it’s a floater or pair looking into taking over an established nest. If they come too close, Rosie, Richmond, or one of the nestlings may sound a guard call, or chase them off the nest. Occasionally there is a more concerted effort on the part of a pair looking for a nesting site, as seen in this epic aerial battle from 2024.

Vocalizations

Vocalizations can have multiple functions. See also “What do the different Osprey calls mean?” on our FAQ page.

Solicitation calls are usually requests for fish, but have also been observed after ample feeding, perhaps depending on context and possibly slight modulation not apparent to us.

Guard calls warn off other Ospreys.

Alarm calls warn off non-Osprey intruders, such as gulls, corvids (ravens more than crows), and humans.